FRANCE PREPARES TO BAN THE BURQA AS CONSTRUCTION OF NATION’S BIGGEST MOSQUE IS LAUDED

|

| Notre Dame de la Garde |

|

| Arab Market in Marseille |

|

| Garlic at the Arab Market |

|

| Vieux Port de Marseille. Photo by David Scott Allen |

|

| Vieux Port in Marseille |

I find all of this very interesting, as I observe it through my American eyes, and I thought that our readers would too. I will tell you what I know, as best I can glean from news sources and friends in France; but, I will leave it for you, dear reader, to draw your own conclusions. And, I would love to hear your thoughts.

France is home for five to six million Muslims. They comprise nearly 10% of the nation’s population and have the widely-cited distinction of being Western Europe’s largest Muslim community. Islam is the second-largest religion in France, growing faster than the officially secular nation’s dominant and deeply rooted Catholicism. (Exact figures are unattainable because France’s secularism prohibits the collection of census data on religion or race.) Most of France’s Muslims come from…

Algeria and Morocco, former French colonies. The largest Muslim concentrations in France are in Paris and its environs (comprising about 50% of the nation’s total), and in the South of France in the area between Marseille and Nice, and in the northern industrial area of Lille-Roubaix-Tourcoing.

|

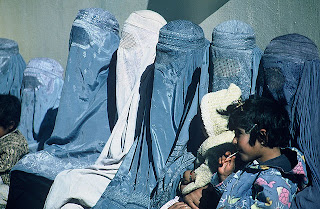

| Women with Burqas |

In all of France, fewer than 2,000 women are estimated to wear the burqa. Technically, the number is much lower because burqas are informally lumped together with the more commonly-worn niqab, even though they are clearly different garments. The burqa is a full-body covering that includes a mesh over the face and eyes; it is not commonly worn outside of Afghanistan and extremely rare in France. The niqab is a full-face veil that typically leaves an opening for the eyes; this piece of clothing is the more frequently encountered than the other full-face covering in France, although the few women who do don the niqab mostly reside in the predominantly Muslim suburbs of Paris. Both of these, because they are full-face coverings, are included in the upcoming “burqa ban.”

|

| Niqab |

It is important to note that the hijab, a much more frequently worn garment that covers the hair and neck but not the face—often cited as an example of a Muslim woman’s “modest dress”—is not included in the upcoming ban. Nor is the chador, which covers the body, but not the face.

|

| Hijab |

What has come to be known as “the burqa ban” will, in effect, expand the 2004 law. It was overwhelmingly passed in both houses of the French Parliament: in July 2010, it breezed through the National Assembly, the lower house, by a vote of 335 to 1 and, in September 2010, it flew through the Senate, the upper house, by a vote of 246 to 1. (In the latter legislative body, most Socialist party members abstained although they reportedly oppose full-face coverings in public but did not want to address the issue in the legal arena.) To ensure that the law would be able to withstand any legal challenges, upon its passage in the Senate, the leaders of both houses requested that the nation’s Constitutional Court review the constitutionality of the law. A month later, in October, the courts determined it to be constitutional (although the law may still be subject to a challenge by the European Court of Human Rights).

What has come to be known as “the burqa ban” will, in effect, expand the 2004 law. It was overwhelmingly passed in both houses of the French Parliament: in July 2010, it breezed through the National Assembly, the lower house, by a vote of 335 to 1 and, in September 2010, it flew through the Senate, the upper house, by a vote of 246 to 1. (In the latter legislative body, most Socialist party members abstained although they reportedly oppose full-face coverings in public but did not want to address the issue in the legal arena.) To ensure that the law would be able to withstand any legal challenges, upon its passage in the Senate, the leaders of both houses requested that the nation’s Constitutional Court review the constitutionality of the law. A month later, in October, the courts determined it to be constitutional (although the law may still be subject to a challenge by the European Court of Human Rights).

According to a CNN World report, “The French Constitutional Council said the law did not impose disproportionate punishments or prevent the free exercise of religion in a place of worship, finding therefore that ‘the law conforms to the Constitution’.” With that ruling, a six-month period was put into place before the law would go into effect in order to inform people of the specifics and penalties for violation of the law. On April 11, six months will have passed, at which time the law will go into effect. (Interestingly, all the people we interviewed were unaware of this implementation date.)

The law, itself, forbids people—French citizens, residents, and visitors, alike—from concealing their faces in public places. Words such as “Islam,” “Muslim,” “women,” and “veil” are noticeably absent in any part of the written law. Exempt from the ban are people who must conceal their faces for work-related reasons (such as those in law-enforcement and other high-risk environments) and those who participate in certain sports (such as fencing). Among the items not included in the ban are motorcycle helmets, ski masks, and carnival masks.

In essence, when the law goes into effect on April 11th, it will be illegal for a woman wearing a full-face veil to step outside her home. Except for private homes, religious settings, and private vehicles (as a passenger or, if her vision is not impaired, as a driver), women will be banned from wearing burqas or niqabs anywhere else.

In anticipation of the new law, this week, French authorities began distributing posters and leaflets that display the slogan, “The Republic lives with its face uncovered” and present the specifics of the law. A website is also said to be in the works, with the URL is www.visage-decourvert.gouv.fr, roughly translated as “uncovered face.government of France. (I have yet to be able to find the site.)

This is what I can piece together about the procedure in the event that a veil-clad woman ventures out in public. Police, who are apparently reluctant to enforce the law, are instructed to prioritize their actions in favor of the urgency of their cases. Managers of shops, restaurants, cinemas, etc. may turn a blind-eye to the veiled woman or ask her to either uncover or leave the public place. If the veil-clad woman refuses to uncover or to leave, the police may be called. The woman may be required to go to the police station, where her identity will be confirmed and a penalty imposed if she refuses to uncover. Ordinary citizens are not expected to patrol public places and are not allowed to force someone to remove her veil.

The penalties for wearing face-covering veils will be stiff: as much as €150 as well as required attendance in courses on “republican values.” Fines of up to €30,000 and one year in prison may be imposed on those who are convicted of forcing a woman—such as one’s wife, daughter or sister—to wear a veil. Forcing a minor to veil herself can lead to a doubling of both the fine and time in prison.

|

| Poster supporting the ban on minaret construction in Switzerland |

A majority of people in several other European countries— Belgium, Britain, Germany, Holland, Italy, Spain, and Switzerland—reportedly support such a ban and, in fact, their governments are reportedly considering such bans. The majority of voters in Switzerland supported a referendum to ban the construction of minarets, the towers on mosques from which Koranic chants are broadcast to call worshipers to prayer. I found it interesting that, last July, Syria banned full-face veils in both public and private universities. In the United States, about two-thirds of those polled in the Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project opposed the ban. Amnesty International is also opposed to the ban.

|

| President Nicolas Sarkozy |

The majority of the French people remain devoutly Catholic (although the Church’s importance is waning); but, as Lyon resident and friend Jean-Paul (real name not used) said, “We are the granddaughter to the Church—Italy is the daughter—we are religious, but our allegiance is to our country.” The French government fiercely protects religious freedom by actively discouraging conspicuous public expression by state authorities (e.g., taking the oath of office with one’s hand on the Bible) and frowning on overt religious expressions by individuals. After the Swiss vote on minaret construction, The Economist wrote that President Sarkozy advised people of all religious faiths to use “humble discretion” while practicing their religion. This approach is contrary to the United States of America’s tolerance—even unofficial popular encouragement—of religious expression by public figures and individuals to achieve the same goal of religious freedom. One may be able to poke holes in the logic of the burqa ban as a mechanism to protect religious freedom, but I feel there is definitely merit to this position. Others, especially Americans, may not agree because of deeply ingrained feelings based on our First Amendment.

Frustrations aside, Richard, like other non-Muslim French I spoke with, was ambivalent, even nonchalant about the upcoming law. “It is based on laïcité—everyone must follow the laws of the country in which they live.”

“Banning the burqa,” for other French people with whom I spoke, is a symbolic gesture that says something akin to, “Like my country or leave it…or, better yet, don’t come at all.” The ban may affect only a tiny proportion of French citizens and an infinitesimal proportion of visitors, but it affects those individuals deeply. The message will be broadcast far beyond the borders of France.

I am not surprised that the burqa has turned out to be the symbolic gauntlet. Symbolic or not, the burqa elicits a powerful and visceral response in many people, both its wearers and those to whom it is unfamiliar. I reluctantly confess that I still remember my first personal encounter with someone wearing a burqa. It was maybe eight years ago, in the coat department of Saks in Boston. I rounded the end of an aisle and nearly ran into a woman who was completely engulfed in opaque black garb, save a 2 x 4 inch rectangle of tightly woven black mesh that hid her eyes. I excused myself, but there was no response from this person: she didn’t speak and, of course, I could not see her face or her eyes. I didn’t know where to look. I had no way of knowing whether the person was angry or forgiving. I found myself thinking of this individual as more creature-like than person-like and realized that I was experiencing a growing panic that was not relieved until the person walked away. I then observed the veiled person make a purchase and could see that the clerk, however pleasant and professional she presented herself, was very nervous. When my turn came around, the young clerk unleashed her feelings of extreme discomfort about her previous interaction.

|

| AP Photo/Claude Paris |

Meanwhile, as we ponder the effects of the burqa ban, work continues on the Grand Mosque in Marseille. The complex, scheduled for completion by 2013, will be 8593 square meters (92,500 square feet) and, in addition to the prayer room, will house a Koranic school, library, restaurant, and tea salon. The minaret will rise 25 meters (82 feet) high. President Sarkozy and the Mayor of Marseille, Jean-Claude Gaudin, are among many French people who hope that the large mosque complex will offer Muslims another path to mainstream France, one they hope won’t include burqas. Mohamed Moussaoui, President of the French Council of the Muslim Faith also seems to be excited about this integration.

The enthusiasm of the Muslim community is palpable and has undoubtedly contributed to the successful navigation of erstwhile obstacles. The mosque’s location: Muslims were not troubled by the location, on the northern most part of the city, a long distance from the historic Old Port (where the Arab market is). The site: the fact that the mosque will replace an old dilapidated slaughter house—of pigs!—that later served as a hang out for drug addicts raised some eyebrows but few objections. The cost: Muslim leaders do not seem deterred by the knowledge that much more money must be raised to meet the €22 million its construction will require. The call to prayer: worshipers do not seem bothered that, in deference to the ethnically diverse neighborhood, there will be no traditional call to prayer from the minaret—no muezzin—typically heard blocks away, five times a day. Instead, there will be a purple light that flashes to call the faithful.

With only four true mosques in the city, Marseille’s Muslims have patiently waited for the Grand Mosque and, when the purple light finally flashes, they will hail from tiny stores, small restaurants, converted garages, and renovated basements that have all bulged at the seams as makeshift places of worship for over 60 years.

Come April 11th, my thoughts will be with all French people as they grapple with the implementation of this law and all the issues that surround it. I will be watching Marseille with particular interest and great hope.

I do find the dichotomy fascinating – that the ban is happening as the mosque is being built. I can also liken it to things that happen everyday in our country… and probably many other places int eh world. There are no easy answers, are there? Thank you for such a thoughtful and thought-provoking article!

David

David,

Thanks so much for your comments.

I learned a lot researching the topic and talking to others about their feelings on the subject. Laws, cultures, religions, traditions, politics, personal beliefs, fears, the economy, ordinary people–when all these factors are entangled, it is very complicated.

Susan

Since seeing an interview several years ago with women who are so comfortable with the anonymity and privacy of wearing a burqa, I can't help wonder if those who will now be forced to put it aside will feel they've been stripped naked and publicly humiliated. While the imminent change might provide a welcome excuse to some who never liked wearing it, others must feel threatened with exposure.

Most immigrants somewhat transform the new place around them, but over the course of a generation or two they and their heirs are more often transformed by their new home. A century ago Americans were terribly fearful of immigrants but they and their children and grandchildren have been transformed by it, and enriched American culture. To take a simple example, think how the American Christmas observance melds British, Dutch, German, French and Italian traditions; and how readily Anglo-Americans join in celebrating Cinco de Mayo or Mardis Gras or Chinese New Year or Mardi Gras. Today, immigrants to America tend to learn English and adopt American ways much faster than did their predecessors a century ago. This is partly due to the permeation of radio and television, and also to the power of the homogenization of national culture we sometimes find ourselves complaining about. Thank you for a very interesting essay.

To anonymous,

I wish that I would hear from Muslim women who wear veils. You mention the role of radio and television–I wonder what role social media will play in that interaction between immigrants and the new culture in which they live. Thanks very much for your thoughtful observations.

Susan

I am ABSOLUTELY against the "burqa" in my country, France. When in France, do as the French do. Hiding oneself in such a costume could be dangerous, as a man could cover himself that way, too, and cause troubles to other people. The "Niqab" shouldn't be used either–except for the eyes ,everything else is covered also. If I were living in an Arab country, should I wear my Sunday hat and go around with my rosary in my hands? I lived in Burkina Faso where people are mostly Muslims, and never saw women wearing such outfits. I lived with Catholic nuns overthere, who dressed as anyone else, only with a chain and a cross around their neck. In this country, Indians don't wear feathers on their heads, except for special feast days. I definitely am for wearing the "hijab" if women who are Islamic Arabs want to feel more comfortable.

Dear Anonymous,

You are not alone in feeling that the culture in which one resides should be the most influential in determining one's dress (as well as behavior). Certainly, you have followed those guidelines when living abroad. Thanks so much for your thoughts.

Susan

Dear Brian,

I certainly don't mind you going on at length….I fascinated by your experience and I am certain that our readers will be very interested as well.

You mention the "jilbab" and suggest that it is similar to the niqab….I am not at all an authority on Islambic clothing, but I don't think that the Jilbab involves a veil. Among other sources, I used http:/islam.about.com/od/dress/tp/clothing-glossary.htm?p=1 as a reference.

Can any reader advise us?

Thank you so much for your thoughtful comments.

Susan

Dear Susan:

I've mentioned to you, I think, that my hometown of Luton has a very large Muslim population and that the Bury Park district where I was born and raised is almost entirely Muslim. There was a case a few years ago brought by a local schoolgirl before the European Court of Human Rights which established her right to wear the jilbab (the same as what you're calling the niqab, I think). The best explanation of this case that I've been able to find on the web is at

Article 14 of the European Human Rights Convention reads:

Article 14: Prohibition of discrimination

The enjoyment of the rights and freedoms set forth in this convention shall be secured without discrimination on any ground such as sex, race, colour, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, association with a national minority, property, birth or other status.

It was with reference to this Article that the case was brought before the European Court and I would imagine that a similar case will be made by some person or organization in France. (If I remember correctly, the case was presented to the Court by Cherie Blair, wife of Tony!).

There was some controversy in England when a Member of Parliament (Jack Straw, who was Foreign Secretary in Tony Blair's last administration) indicated that he was uncomfortable seeing constituents at his constituency office if they were wearing dress which covered the face, and would ask them to uncover the face. How this was resolved I don't know.

For many years, throughout the nineties, Luton had the largest mosque in Europe outside European Turkey. It was built on the site of the Co-op store where as a child I used to shop with my mother. If you still have the NY Times article I sent you at the time of the general election last May in the UK you'll see there a photograph with the minaret appearing above the other buildings.

Luton is now notorious as a hotbed of radical Islam, though that contention is hotly disputed in the town. It is said (and I'm pretty sure that in general terms it's correct) that relations between the communities are very good and that militants are a tiny minority. Nevertheless the town has the distinction, if that's the right word, of having had more residents die fighting for the Taliban than for NATO forces.

The town made headlines (including the NY Times and the Washington Post) again last December when a militant Muslim from Luton blew himself up in Stockholm. My favorite headline was "How Luton Became the Epicentre of the Global Clash of Civilisations." You can follow this article at http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/how-luton-became-the-epicentre-of-the-global-clash-of-civilisations-2159578.html.

As far as I know there has not yet been any general call for banning the "burqa" in the UK, and it seems not to be a major issue. The far-right anti-Muslim groups who fought last year's general election received derisory votes (not that this has always been the case, particularly at local level), and that has certainly not been the case in, say, France, Netherlands, Denmark and even Sweden.

I hope you don't mind me going on at some length, but my guess is that you'd be interested. It's a big subject.

Talk to you soon ~ hugs, Brian.

I'm completely against this ban. The Burqa for some Muslim women is their identity. What happened to freedom of expression??? It's becoming stupid how can a government control what a woman wears?! It's outrageous!! It's against human rights! What happened to free will?!?!? I am a Muslim woman myself and I know how difficult it is nowadays to practice Islam in the western world.

Words seem to fail me when I try to explain my views on this. I just feel so angry and frustrated at the fact that this can happen HERE in the western world. I'm sure this is a form of oppression! I feel for the Muslim sisters in France who wear the Niqab. So what if only so many women wear it they're wearing it because they want to because its how they want to dress, it's how they express their beliefs how can they take that away from someone?! This will affect every muslim out there and every person who stands for human rights.

I stress these are just my views and how I look at this subject.

From a rambling concerned sister

Raisah x

Dear Raisah,

Thank you so very much for your thoughts. I think that, without meaningful dialogue with people who practice Islam, it is hard for those of us in the West to understand how important wearing the Islamic veil is for Muslim women. You can see that there are many different views expressed here on the subject.

In your video, you provide a very moving testimony for your wearing of the hijab. Readers who want to see Raisah's video can go tohttp://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F05_BVmGnYg

Please check back and let us know when part II is out!

Thank you for posting your views.

Susan

Here's part 2 (i)

part 2 (ii)

part 3

Part 2 and 3 is about voicing other peoples opinions I hope this helps people understand how important hijab/niqab is for a muslim woman who wears it. Despite people voting 'yes' on the ban does not change the fact that niqab/hijab is part of a woman's identity and it's who they are and what they're about.

Raisah x

As an agnostic and, I hope, a tolerant individual, I am sympathetic to those Muslim women who have been raised to believe it a tenet of their religion and culture that they keep their face and body private from public view, but are now told they will be acting unlawfully in France if they continue to do so.

However, as a UK citizen, and an inhabitant of London as well as our home in the Luberon, I see at first hand the increasing concern and sometimes outright hostility towards Islam in the UK.

The UK is a country which, like France, has welcomed and assimilated newcomers for centuries. Unfortunately,there is a growing groundswell of resistance to Islam, perhaps fuelled by recent history, but certainly exacerbated by the behaviour of some extremists who exercise their right to freedom of speech in the UK by threatening and reviling the country in which they have chosen to live, while at the same time happily and cynically playing the benefit system. Like it or not, the burqa is the outward and, to some, unacceptable face of a religion many people fear.

The pendulum of tolerance has to be seen to swing equally in both directions. If apparently preferential treatment is given to one religion over another, there is bound to be hostility. It's not so long ago that a BA employee was removed from her position for refusing to take off the small silver cross she wore around her neck. In another case, a woman hospital worker was cautioned for causing offence by saying she would pray for a patient. Just like the burqa, these were external manifestations of religious belief, but those women were disciplined for demonstrating openly that they held religious views. Why, then, should the burqa be treated differently?

If an individual categorised as a 'Westerner' visits the Middle East, for example, it's expected that the non-alcohol rule is observed and that Western behaviours and dress are modified out of respect for local observances. Those who ignore or flout these conditions are likely to encounter rough justice. So, it seems that in the Western world, women of Islam have the right to wear a burqa, but I, as a Western woman in an Islamic country, can't enjoy a glass of wine or greet a male friend with a kiss on the cheek. Why is that not discriminatory?

If you choose to live in a particular country, it is your right and privilege to continue to live your life according to the rules of your religion in your own home and at your chosen place of worship. It is not your right to try to impose those rules on the wider community in your chosen country, and expect the members of that community to change to suit you. I have many Jewish friends, some of whom keep a Kosher house. When I visit them, I eat a Kosher meal. When they visit my home, I cook them fish and serve it on a paper plate. In other words, we adapt to our surroundings and everybody's happy.

I agree with you. The customs and laws of a country should be respected by the"guests" of that country. The law had a due process that was followed and a representative majority of French citizens apparently support the passing of the law. I think your example that visiting a middle eastern country that has its own restrictions for Westerners that should be respected by visitors is relevant. Here is perhaps a humourous way of looking at the situation but in reverse. What if I defined nudism as a tenet of my religion, should I be allowed to promenade in the buff in public? Should this forbidding this act be seen as undermining freedom of religion? Not likely to pass muster in any country!

Thank you to the above two anonymous writers for taking the time to post such thoughtful comments on this complicated and arguably personal subject. It seems that, however central the Islamic veil is to some Muslim women, when one chooses to live in or visit a country (in this case, France)that abides by laws based on a philosophy that does not support conspicuous public display of ANY religion (laïcité), those who wear burqas and niqabs must,like everyone else, abide by those laws. There are no grounds on which the Islamic veil may be an exception.

Recognizing the importance of the veil to some Muslim women will encourage sensitivity in enforcing the upcoming law.

I welcome other perspectives, observations, and questions.

Thank you very much.

Susan

Dear Raisah,

I welcome your response to the recent comments. How can wearing the Islamic veil in the deeply secular nation of France, with specific laws that prohibit wearing it, be justified? Help us understand your perspective.

Thank you.

Susan

I support the ban, only because the French government's rationale makes perfect sense. In a country that does not view being French to be an issue of "color," but in culture, it welcomes everyone who seeks to live the French way of life. They do not spout platitudes of inclusion that aren't borne out by history. Because other nationalities are bound to the same restrictions, it is no discriminatory. People should seek to live in countries that have the same beliefs, or adjust to countries that welcome them, but want no part in the debate. Excellent article.

Dear Anonymous,

Thanks for your kind feedback about the article. Very interesting point regarding "color," a characteristic that is the primary source of discrimination in many countries. In France, I think you are saying, color is not an issue–it does not determine who is welcome or even define being French–"culture" and "wanting to live the French way of life" are what makes the French French. Everyone is "bound by the same restrictions." Very different from our country. Neither approach is better, just different.

Thanks again.

Susan

This is an excellent article, diligently researched and thought provoking. My immediate reaction as an American, who deeply values freedom, living amidst American citizens who have become increasingly apathetic and recklessly give up individual freedoms seemingly without thought, was shock. My thought was, of course, the personal freedom of expression should be respected. Then, I read on.

There is no simple answer and perhaps no absolutely correct answer. When in a country that is not my own, I am respectful of the culture and in fact, willing to observe and participate as fully as allowed with the dress, customs, foods, music, home stays because it is then that I learn the most about the people. It is in this type of interaction that I am familiarized with the similarities of humankind, which I believe builds bridges. It is my theory that if one is not actively engaging with the people of a locality, there is a tendency to observe all the ways in which we are different from one another, which is constructive only in building walls.

Having visited France on a number of occasions has enhanced my desire to strive to live the "French way of life", or my perception of it, wherever I am. But does the "French way of live" mean working less, playing more, lingering over delicious meals with friends and family, wine with more than just dinner, coffee served with a small square of decadent dark chocolate enjoyed indulgently in an out door cafe while enjoying the colorful, fashionable, creative, playful yet impossibly thin French people, a diverse blend of melding cultures /ed moving through the course of their day? Isn't it most probable the "French way of life" is interpreted differently person to person.?

As most know who have had the opportunity to live in another country, the living is far different from the visiting. Especially if the visiting is limited to role of the tourist. Take another look, perspective, if you will. Imagine you are a stranger is a strange land perhaps by desire, maybe as an act of desperation, or the means to a better life and education for you children. You then find that your customs, your religion, your culture, your traditions, all that you have known must be altered to fit this new society. In addition to learning a new language because, not only, are you not understood, you don't understand, you must learn to curtail your dress, to within the confines of your home or your place of worship. You have been a woman hidden from public view, always. Now, in this strange land, you are not allowed to be covered, to be shielded from view, to be anonymous. And it is meant to be "less revealing" of your "identity" in this strange new land. Unnerving, unsettling, this "understanding".

the thoughts of a poor, wayfarin' stranger travelin' through this world of. . . .

Un grand merci to Audrey, one of our readers, for catching the typo in the website mentioned above. To access the French government's website detailing the ban of face-covering Islamic veils, go to

Of course, the ban has now gone into effect. We will update our readers when possible. Follow us on Twitter for up-to-date information.

Susan

Thank you, Wayfarin' Stranger for your comments highlighting the difficulties of living in another country. Like most controversies, there are two sides–and even more–to this story.

Susan

Your readers may be interested:

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1375654/France-burka-ban-Two-arrested-Paris-protest.html?ito=feeds-newsxml

This is an excellent article, diligently researched and very thought provoking. My immediate reaction as an American, who deeply values freedom, living amidst American citizens who have become increasingly lethargic and recklessly give up individual freedoms seemingly without thought, was shock. Of course, the personal freedom of expression should be respected. Then, I read on. There is no simple answer and perhaps no absolutely correct answer. When in a country, not my own, I am respectful of the culture and in fact, willing to observe and participate as fully as allowed with the dress, customs, foods, music, home stays because it is then that I learn the most about the people. It is in this type of interaction that I am familiarized with the similarities of humankind, which I believe builds bridges. It is my theory that if one is not actively engaging with the people of a locality, there is a tendency to observe all the ways in which we are different from one another, which is constructive only in building walls. Having visited France on a number of occasions has enhanced my desire to strive to live the "French way of life", or my perception of it, wherever I am. But does the "French way of live" mean working less, playing more, lingering over delicious meals with friends and family, wine with more than just dinner, coffee served with a small square of decadent dark chocolate enjoyed indulgently in an out door cafe while enjoying the colorful, fashionable, creative, playful yet impossibly thin French people moving through the course of their day? Isn't it most probable the "French way of life" is interpreted differently person to person.? As most know who have had the opportunity to live in another country, the living is far different from the visiting. Especially if the visiting is limited to role of the tourist. Take another look, perspective, if you will. You are a stranger is a strange land. Your customs, your religion, your culture, your traditions, are all you have known. Now, in addition to learning a new language because, not only, are you not understood, you don't understand. You must learn to curtail your customs, your dress, your habits to within the confines of your home or your place of worship. You have been a woman hidden from public view always. Now, in this strange land, you are not allowed to be covered, to be shielded from view, to be anonymous. And it is meant to be "less revealing" of your "identity" in this strange new land. Unnerving, unsettling, this "understanding".

the thoughts of a poor, wayfarin' stranger travelin' through this world of