THERE’S MORE THAN ONE D-DAY

June 6th marked the 70th anniversary of the Allied landing on the beaches of Normandy. I got a message early in the morning from good friend and retired Marine Bob Finneran, reminding me what day it was. But, I didn’t need reminding.

I, like many people of a certain age, tuned into the live broadcast of the international ceremony marking this occasion from Ouistreham beach—code named Sword beach—in Normandy. I watched the heads of state of the world’s most prominent countries as they arrived and were escorted along the red carpet to exchange greetings with President Hollande and shake hands with a small group of D-Day veterans. These veterans, the real stars of this event, are part of a dwindling brotherhood who knew these beaches when the waters were red and the sand was strewn with bodies of fellow soldiers. I wondered how much, if at all, time had erased those scenes from their memories or whether the neural pathways of those horrific events were just too deeply carved into their psyches—would the horrors they witnessed accompany each man to his grave?

I listened to the well-crafted speeches reminding me that no one knew with any certainty whether this massive invasion into the direct line of German fire would be successful. I think we too often forget this. I was moved to tears by the poignant stories of the now elderly men who landed on those beaches, 70 years ago, when they were in the prime of their lives.

“D-Day” was what this landing came to be called—as if there had been no other “D-Days” before and would be no others thereafter—such was the gravitas of this pivotal military operation. It was the beginning of the most intensive effort by the Allied nations to liberate France and Europe from Nazi occupation. The War would go on, but it was the beginning of the end for the Nazis.

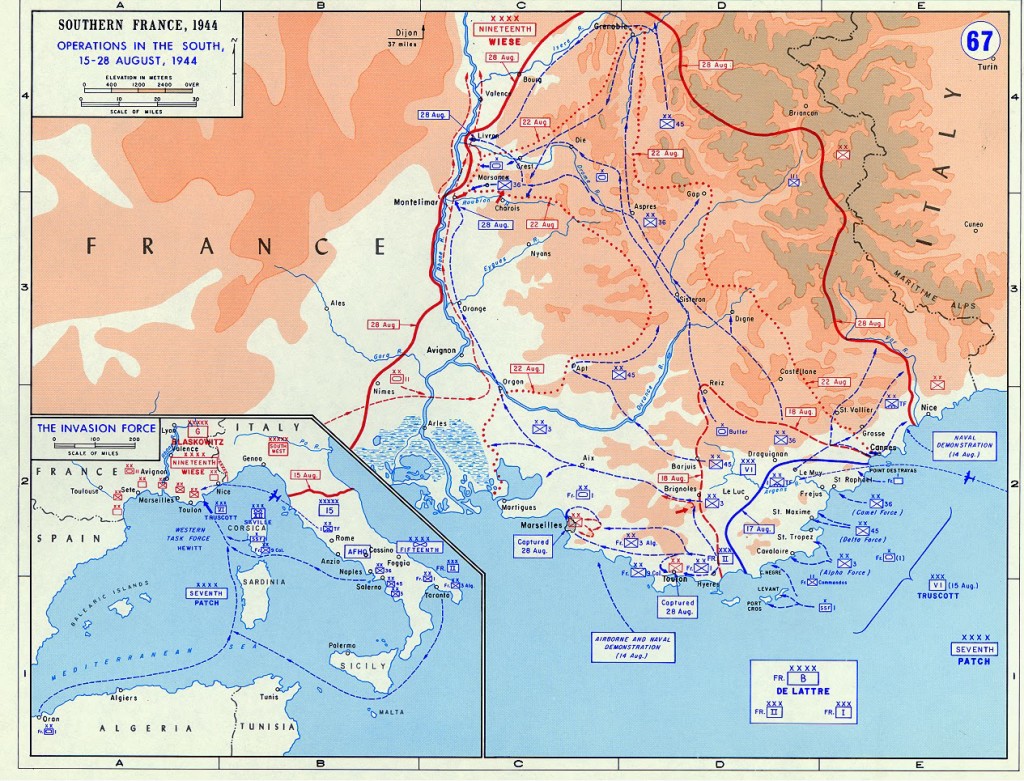

Two months later, on August 15, another “D-Day” took place that would further hasten the demise of the Nazis as well as the Vichy regime. Dubbed “the other D-Day” or “the forgotten D-Day,” this was much smaller in scale than Normandy but instrumental in freeing southern France. Operation Dragoon, as it was code-named, included bombardment from the air, attacks on land, and a massive amphibious operation that focused on three Mediterranean beaches—Cavalaire-sur-Mer, Saint-Tropez, and Saint-Raphael. The mother of one of our friend’s in Lourmarin showed us old newspapers she had saved, and told us her story of this operation, including her husband’s work in the Resistance movement in Provence.

The Germans began to retreat August 17; Paris was liberated August 25; and the war ended in Europe in the spring of 1945.

The Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial in Colleville-sur-Mer, Normandy, France. Photo by W.T Manfull

In Normandy, Provence, Paris, and across the rest of France, World War II remains a part of the conscience collective. Regardless of one’s age, it seems every French person knows their country’s history, including the human, societal, and economic costs and sacrifices of war. The French people I know appreciate that history could have taken a different course and are never far from a primal shudder at that thought.

Not long after 9/11, my family and I were in Provence. While shopping in the pet supply aisle of an Hyper-U (similar to a Target, I suppose), a young man struck up a conversation about dog collars with my daughter and me, thinking we were French. When he realized we were American, he immediately told us how upset he was that our country had suffered so much in the 9/11 attacks. His eyes welled up as he said that he spoke on behalf of all French people when he expressed the immense gratitude that he and all of France will always have for the American role in ending WW II. “We may not like President Bush but we love America,” he said, smiling broadly.

War is part of the French landscape, yes, but their children’s education ensures that generations born long after WW II—like this young man—will never forget even what they did not endure.

The Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial in Colleville-sur-Mer, Normandy, France. Photo by W.T. Manfull

In striking contrast, on D-Day this year, I was saddened by an interaction I had on this side of the Atlantic. It happened in Boston but it could have happened anywhere in our country. I was still thinking about the ceremony I had just seen and I mentioned D-Day to the young woman who rang up my latte. She looked at me, puzzled, and then said, “Oh, you mean doughnut day?”

Not wanting to embarrass her—she seemed very nice—I acknowledged that yes, I did hear something about Dunkin Donuts and Krispy Kreme giving away doughnuts to mark “doughnut day.”

What I didn’t know until later was that National Doughnut Day actually dates back to another war—WW I—when the Salvation Army delivered doughnuts to soldiers to improve morale. In 1938, as part of one of their fundraisers, the Salvation Army officially recognized this effort and somehow Doughnut Day was born. I wish the story stopped here, but it doesn’t. Somewhere along the line, the national chains got on board—not for philanthropic purposes, to be sure, and doughnuts are not “given away” without a purchase—and now its origin has been largely forgotten. Worse yet, it is confused with D-Day.

Doughnut Day is the first Friday in June and, this year, happened to coincide with D-Day. Ah-hah. When I read that 60% of Americans do not know that June 6 is the anniversary of D-Day and 25% of Americans do not know that D-Day took place in WW II,** I understood the young woman’s confusion. “Doughnut” does begin with “D”.

I feel fortunate that I grew up with parents who took my brother and me to see history firsthand. In California, where, fortunately, there was little evidence of WW II,*** we heard stories about it. My grandparents were “airplane watchers” and would work from high towers along the beach in Half Moon Bay. My grandfather was an “air raid warden” whose task was to wander their neighborhood to ensure that all curtains were tightly drawn to make the area completely black and invisible to aircraft flying over.

I was riveted by my mother’s stories of childhood dinners eaten under the table with only a candle for light; collecting rubber and metal products; waiting for rationed goods like meat, sugar, and coffee; and making posters in art class to promote the donation of old girdles to the war effort. It would be many years before I understood how my mother’s war efforts related to the events in France and Europe, but I knew about D-Day long before I ever heard about Doughnut Day!

The Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial in Colleville-sur-Mer, Normandy, France. Photo by W.T. Manfull

If you are taking your children to France this summer, weave a little history into the trip. (It is hard not to do, especially in France.) With the 70th anniversary of the two D-Days falling in this year, WW II would work nicely. Its tentacles reach wide and run deep throughout this country.

In Normandy, stroll along the landing-beaches, climb into the German bunkers, and view the War Cemeteries— the American Cemetery and Memorial, where nearly 10,000 American soldiers are buried is stunning— and visit one of the many museums nearby.

The Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial in Colleville-sur-Mer, Normandy, France. Photo by W.T. Manfull

In Provence, visit the recently opened the Camp des Milles, France’s only remaining internment and deportation camp. I plan to visit this important site—museum, memorial, gallery, and what remains of the camp itself—this summer.

Camp des Milles. Source: http://www.campdesmilles.org/index.html Camp des Milles. Source: http://www.campdesmilles.org/index.html

In Paris, when you and your children visit the Louvre and gaze upon the Mona Lisa, tell them that, in 1939, it was bundled up and carted away by ambulance so that it didn’t fall into Nazi hands (or become a casualty in Allied bombings). It moved no less than six times during the war, staying safe in various countryside châteaux. It was never found by the Nazis.

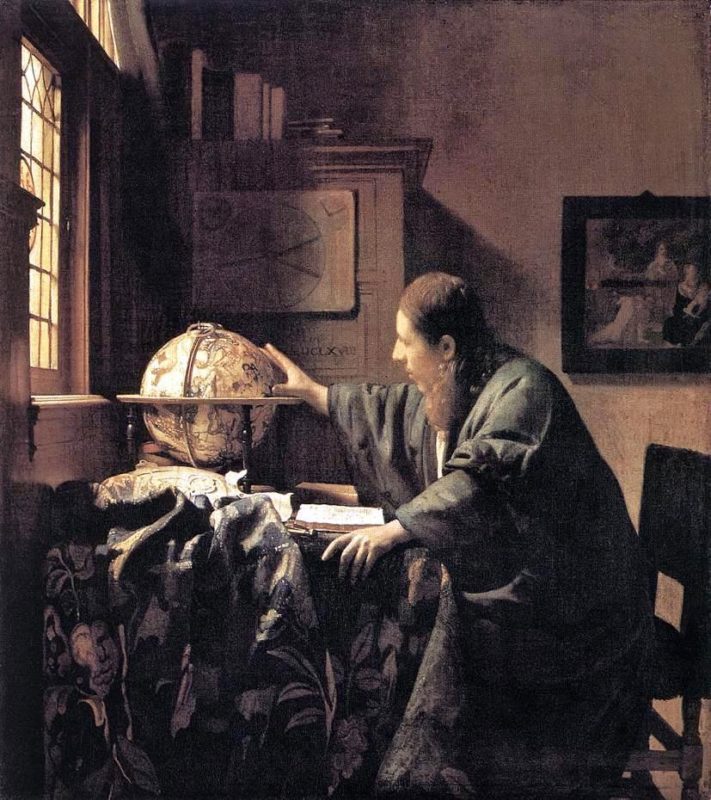

As you admire Vermeer’s The Astronomer, explain to your children how fortunate they are—we all are—to see it hanging in the Louvre today. In 1940, it was stolen from the Rothschilds’ hotel room in Paris, taken to the Jeu de Paume (a National Gallery not far from the Louvre, adjacent to the Jardin des Tuileries) which had been turned into the center of the Nazi looting operation. There, it was designated for Hitler’s museum and transported to one of his holding areas in a salt mine in Altaussee, where, in 1945, it was rescued by the “Monuments officers” and returned to the Rothchilds who eventually donated it to the Louvre. A small swastika and Nazi inventory code remain on the back of the painting. About 3,690 paintings, as well as sculptures such as the Venus de Milo, were evacuated from the Louvre in 1938 and ’39.

If your children want to know who was instrumental in helping the Monuments officers find some of the millions of pieces of art, pillaged from Jewish families and museums throughout Europe, go to the Jeu de Paume and look for a small plaque on the southwest corner of the building, near the Place de la Concorde. There, you will see Rose Valland’s name, the French art archivist who was forced to work in the Nazi looting operation in this same building; in this role, she secretly kept meticulous records of the location of each piece of stolen art that passed through the Jeu de Paume. Based on her records, much of that art was recovered.

Tell your children stories about the real D-Days. Start before you leave on vacation.

The Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial in Colleville-sur-Mer, Normandy, France. Photo by W.T. Manfull

_________________________________________

Notes:

*Please see an earlier TMT post for more on “the other D-Day” in Provence and watch for an upcoming post about Camp des Milles.

**This information comes from a recent survey conducted by The American Council of Trustees and Alumni.

***Today, the Japanese internment camps would be included as evidence of WW II.

Michelin has released reproduction (1947) maps of the battles of Normandy and Provence. They may be ordered here: Michelin Battle of Provence Map No. 103

Very, very well-written reminder…merci.

I loved this! Thank you….

Thank you…wonderful article and the history about the other d-day in August. On our bucket list to visit Normandy and spend a couple days to see the memorials, tributes, the small fishing village and the historic countryside. Yes, the French and Italians do revere their heritage. Our country is so vast and spread out, we don't have the same sense of a collective, shared history.

Beautifully written, Susan. If it helps you, I am a foodie and I didn't know it was Doughnut Day. I think it is very important to keep days like D-Day alive in our minds, lest we forget and let something terrible happen again. History does repeat itself, unless we keep it from doing so.

A very good and thoughtful post. I've always been impressed when I've visited Normandy about how the French people take their young children to the American cemetery so that each generation never forgets the sacrifices that were made to free their country and Europe.

This is an email I recently received: Beautifully

written and thought provoking for many reasons. Countless times I have

shared with people in conversation the experience of visiting Normandy

with my children, though not on D-day. In all the travels with my

children this visit will always be one of the most significant.

Remembered for its excellence in educating visitors of the events that

unfolded here during that WWII invasion (more thoroughly, more

personally, more interactively) and decades earlier than any in the

U.S.) and continues to speak volumes of the gratitude on behalf of the

peoples saved. This point was driven home to the three of us when we

were each

briefly embraced by a woman of my parents' age when she noticed the

tears in my eyes as she started to pass by us. Our visit happened to be

on a day when classes of older primary school children were there. Each

student had a small book on various world leaders – Stalin, Mussolini,

Marx, Kennedy, DeGaulle, Hitler, Churchill, etc. I will never forget the

engagement between the teachers and the students and wondered if it was

partly due to the historical significance of this backdrop. A French

soldier walked with us for a while and explained that it is a sight to

see the one day each year when American soldiers return and walk through

the crosses accompanied by school children, usually hand in hand. My

son did make the comment in the car after leaving – "I don't think the

French hate us."

Moreover

I picked up your subtle statement that here we are with US soldiers in

dangerous places maintaining world safety while the citizenry reaping

the benefit are barely affected, too busy to be supportive and choosing

"reality" tv over being updated on world news/events. So sad