Sel d'Aigues Mortes. Photos by W.T. Manfull

Sel d'Aigues Mortes. Photos by W.T. Manfull

And, when they’ve had their fill of historic Aigues-Mortes and its neighboring salins (salt marshes), there is the whole Camargue at their disposal—a Parc Naturel Regional of over 140,000 hectares (500 sq mi) filled with pink flamingos, white horses, and black bulls, among other wildlife and a beautiful landscape.

Spring is the best time to visit, when the flora and fauna come to life again and before the throngs of people and mosquitoes descend in the summer.

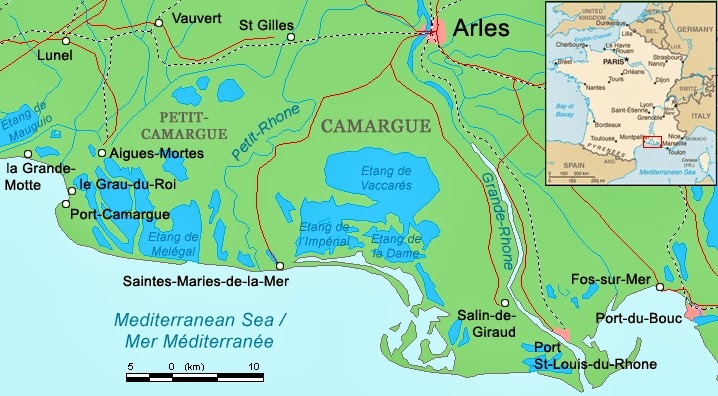

Map of Camargue. Wikipedia.

Aigues-Mortes is located in the southwest corner of the Camargue, the name given to Western Europe’s largest river delta. The mighty Rhône River, one of Europe’s major rivers, travels 813 km (505 mi) from the Swiss Alps to Arles, where it divides in two—the Grand Rhône, on the east, and the Petite Rhône, on the west. The two tributaries continue on to empty in the Mediterranean Sea.

The land west of the “Little Rhône” is referred to as the “Petite Camargue” and lies in the Gard

département in the neighboring region of Languedoc-Roussillon—Aigues-Mortes is in this part of…

the Camargue. The rest of the Camargue lies within the

département of Bouches-du-Rhône in Provence.

Most tour books on Provence include Aigues-Mortes—as well as Nîmes, Uzès, and the Pont du Gard, all of which rest just across the line in Languedoc-Roussillon—because it is definitely worthy of your consideration on your vacation in Provence.

Rick Steves, in one of the few instances in which I disagree with his recommendations, advises travelers to “skip [Aigues-Mortes] unless you need more souvenirs and crowded streets” although he adds that a detour might make sense if you are in the area. I initially shared his sentiments; when we first went to Aigues-Mortes, en route from Montpellier to

Lourmarin, it was around Easter and it was excruciatingly crowded.

|

| Aigues-Mortes. Photo by W.T. Manfull |

I

wrote, “It is really a shame that the well-preserved thick walls and tall towers that surround this 13th century city can’t be used to protect it from the hordes of tourists that descend upon it every weekend” and in the next sentence made reference to “the tacky stores that line the medieval streets.”

Subsequent trips changed my mind. Regular readers of TMT know that I am smitten with the Luberon, but for a taste of the “sauvage” part of the South of France, I would definitely recommend Aigues-Mortes and the Camargue. In the hour-and-a-half drive (50 km/80 mi) from Lourmarin, for example, you will feel like you have traveled much farther, crossing the border into a foreign land.

Don’t let its name deter you. Aigues-Mortes evolved from “Aquae Mortuae” (Latin) and “Aigas Mortas” (Occitan, the old Provençal language) and literally means “dead waters” or “stagnant waters.” Back then, when the town was christened, there wasn’t much more to Aigues-Mortes than its marshes and swamps, and the name also underscored the lack of potable water in the area.

Today, you will see that there is much more to Aigues-Mortes than marsh land; in addition, it is important to note that those salt marshes are instrumental in preserving the biodiversity of the Camargue’s plants and animals. Still, the city is stuck with its unflattering name.

As I wrote in

the previous post, “La Carmargue Sauvage,” there is some evidence of human habitation going back to the Neolithic period. Later, beginning about 1,000 AD, not surprisingly, the usual groups made their way to this area: the Ligurians followed by the Greeks and then the Romans came through, mainly to extract salt and do some fishing. The city is said to have been founded in 102 BC by the Romans. In the 5th century, Benedictine monks moved in, established the Abbey of Psalmody, and ruled over the land.

|

| King Louis IX |

Aigues-Mortes wasn’t really on the map until the early 13th century when the King of France, Louis IX, needed access to the Mediterranean to launch a crusade. As the story goes, around 1244, the very pious King, suffered a serious bout of dysentery and apparently made a promise to God that if he recovered, he would devote the rest of his life to the preservation of Christianity. With that in mind, after his miraculous recovery, he wanted to launch a crusade and wanted a French port on the Mediterranean from which to do it.

At that time, the kingdom of France had no Mediterranean seaport. The geographically logical Marseille port was ruled by the Counts of Provence (separate from the French Kingdom), Agde was ruled by the Counts of Toulouse, and Montpellier by of the King of Aragon, leaving the King Louis IX with few options.

However, he was able to strike a deal with the Benedictine monks who owned most of the “dead water” land around Aigues-Mortes. Upon obtaining a portion of land with access to the sea (via a channel), he began to encourage settlement by offering tax exempt status to would-be residents (who would then have unrestricted access to salt). He built a new town (the original grid plan is still visible) and constructed two towers, the Carbonnière Tower (as a watch tower) and the Tour de Constance (to house his troops). Most importantly, he established his port and in 1248, about 1500 ships—filled with an estimated 35,000 men and their horses and equipment—set sail for Cyprus in what came to be known as the Seventh Crusade. The king returned from that crusade some ten years later and set sail again in 1270 for the Eighth (and final) crusade, known as the Crusade of Tunis. There King Louis died. Twenty years after his death, he was canonized.

Tour Carbonnière. Photo EmDee

When the King died, only the barest outline of the ramparts were in place, so his son, Philip III (the Bold) and his grandson, Philip IV (the Fair) finished the walls by the early 14th century. Aigues-Mortes enjoyed a short period as a successful port with ships from as far as Constantinople and Antioch and a permanent population of as high as 15,000 (compared to today’s 8600 inhabitants). But, it wasn’t long before the channels from the sea to the city silted up and, with the unification of Provence and France (in 1481) and consequent opening up the rival port of Marseille, Aigues-Mortes’ role as a port declined in importance.

|

| Tour de Constance. Photo by W.T. Manfull |

At the same time, the city succumbed to the dissent that affected the rest of France during the 14th century. During this ignoble period of history, the Tour de Constance was used for a prison for the Templars in the early 14th century. In the early part of the next century (during the Hundred Years’ War), it was used as a mortuary for Burgundians (slaughtered by the Armagnacs in a surprise attack); each layer or corpses was salted to preserve them for burial, causing the tower to be dubbed “Le Tour des Bourguignons” and inspiring a nursery story about “salted Burgundians.” In the early 18th century, female Huguenots (Protestants) were imprisoned in the Tour de Constance (one Marie Durant for nearly 40 years); and at the end of the 19th century, there was the “Massacre of the Italians,” referring to an uprising in which as many as 17 Italian salt-harvesters were killed and 150 were injured.

The silver-lining to the collapse of the port facilities and consequent economic decline in Aigues-Mortes is that the city itself, having survived several tumultuous centuries, is remarkably well preserved today. Certainly its challenging location also played a role, but unlike other parts of Provence where historically and architecturally significant buildings, including many dating back to the Romans, were dismantled for other purposes, the fortifications initiated by Saint Louis remain intact and largely as they were in the 14th century.

It is not surprising that over a million tourists visit Aigues-Mortes each year. Today, tourism along with agriculture—salt and wine—are the major sources of revenue for Aigues-Mortes.

If you are planning a visit to Aigues-Mortes, here are a few of my recommendations:

As I wrote above, visit in the spring (but not around Easter) or in the fall. There are fewer people and mosquitoes (compared to the summer) and the weather is nicer (compared to the winter when the bitterly cold Mistral is likely to roar down the Rhône). In the Camargue, spring is especially inviting when wildlife is re-emerging and the landscape is in full bloom.

|

| Pink Flamingos in the Camargue. Photo: Andrea Schaeffer |

Begin by driving around the ramparts. Two of the walls are adjacent to empty fields, giving the visitor a sense of what Aigues-Mortes must have looked like 700 years ago. Spend some time from this vantage point and imagine transporting all those stones from quarries in Provence–Les Baux and Beaucaire—through the waterways to Aigues-Mortes. The ramparts were classified as a “Monument Historique” (National Heritage Site) in 1903.

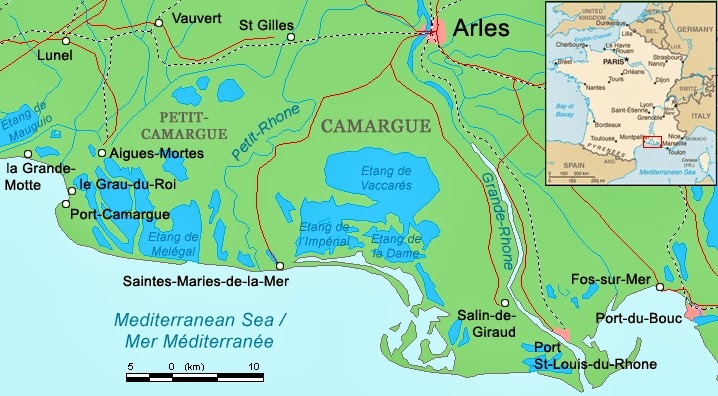

Porte de la Gardette, the main gate, is a good way to enter as it is near the Office of Tourism and will place you on rue Jean Jaures, where you can head straight for Place Saint Louis. There, King Louis IX is immortalized as a lovely statue (1849) overlooking the place which, today, is surrounded by cafes.

|

| Aigues-Mortes. Photo by W.T. Manfull |

The Eglise Notre-Dame-des-Sablons (Lady of the Sands) is adjacent to Place Saint Louis. This is the oldest building in Aigues-Mortes—the original church dates back to 1183. King Louis IX and the other crusaders were blessed here before departing for the Seventh Crusade in 1248. Its roof collapsed in 1634; it was reconstructed in 1711; and beginning in 1991, 31 contemporary stained-glass windows were installed.

|

| Eglise Notre-Dame-des-Sablons. Photos by W.T. Manfull |

Take some time to stroll along the cobblestone streets of Aigues-Mortes. Yes, this city has more than its fair share of tacky stores, but interspersed are galleries and specialty food stores where you can find “Fleur de Sel de Camargue” (and related accouterments from which to serve salt, grind salt, and shake salt), riz rouge, Vin des Sables (wine of the sands), and local delicacies like saucisson de taureau (yep, bull sausage) and “Fougasse d’Aigues-Mortes,” a sweet, buttery brioche with sugar and orange flower water (that might be a more broadly appealing local treat than the bull sausage). With salt being so prevalent, bakeries feature cookies and candies sprinkled with salt from the Camargue.

|

| Fleur de Sel from Aigues-Mortes. Photo by W.T. Manfull |

The ramparts–including the Tour des Bourguignons, Tour du Sel, and Porte de l’Organeau—and the massive Tour de Constance are must-sees. You can choose whether to do this on your own with a guidebook or with a self-guided audio tour, or with a tour guide. Note that there are ten gates in the ramparts, only two of which are on the north side and five on the south side, facing the sea—do you know why? The Tour de Constance, considered a “Masterpiece of Gothic Rationalism,” is, I can attest, a wondrous feat….how did the engineer incorporate all that stuff—stairways, fireplaces, a chapel, an elaborate defense system and more—in a 40 meter/13 foot high circular tower that is 22 meters/72 feet wide with walls 6 meters/20 feet thick? What are all those openings in those thick walls of the tower for?

|

| Ramparts of Aigues-Mortes. Photo by W.T. Manfull |

The view from atop the ramparts or from the watch tower of the Tour de Constance is breath-taking. On the south ramparts, looking out toward the Mediterranean, the sea salt comes wafting toward you and reminds you that Aigues-Mortes stands here because it was France’s link to the sea. In the other directions, you can see salt, one of the primary reasons Aigues-Mortes still stands here and one of the main draws for David (although knowing Mark’s interest in the history of food, I know he would like this tour, too!).

|

| Saltworks at Aigues Mortes. Photo by K. Weise |

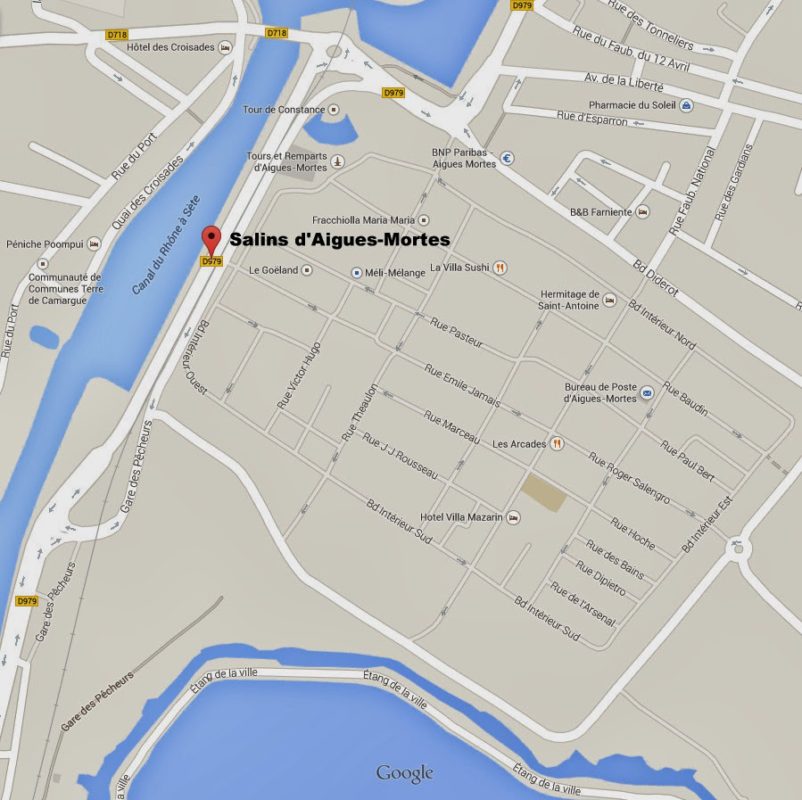

To get a close-up look at Camargue’s salt industry—and for a fun afternoon, head over to Salin d’Aigues-Mortes (also referred to as Salins du Midi), just outside the walls on the west side (see map below). There, as of the first week in March, you can board a train for an hour-and-a-half tour of the salt marshes, a surface area likened to that of Paris, about 10,000 hectares (38 square miles). About 340 km (211 mi) of roads and paths meander and crisscross throughout this area.

In an average year, about 500,000 tons of salt are produced here—half of France’s salt supply comes from here. All of the salt produced here, according to someone I spoke with at Salin d’Aigues-Mortes, is for the table and not the road. (On the other side of the Camargue, in the southeast corner near Salin-de-Giraud, lies another major center for salt production that provides salt for industrial purposes, like melting ice on the roads!).

|

| La Baleine always handy in our cupboard. Photo S. Manfull. |

La Baleine (common) table salt (the blue cylindrical container with the big whale emblazed on it) comes from here as does Fleur de Sel de Camargue, the hand-harvested tasty, coarse flakes that melt in your mouth and command a pretty price.

A picture speaks a thousand words—and my mother is always telling me that people don’t want to read so much—so I encourage you to watch this video below to get an idea of what you would see on the tour. Tours in 4×4 vehicles begin in mid-April and offer a more in-depth visit of the salt marshes.

For those especially interested in the Fleur de Sel harvest, I recommend another 4×4 vehicle tour of that harvest (from mid-July to August). This is also the time of year when the marshes turn pink (due to the high concentration of red marine phytoplankton (microalgae). In the meantime, see the video below showing the Fleur de Sel harvest. (It is in French, but all you need are the images!)

There is also a salt museum where one can find further information about the stages of salt production and its history in the Camargue. There is also a small store, mais oui, where salt and various accouterments may be purchased (great gifts for family and friends!).

According to my source from Salins d’Aigues-Mortes, about 90,000 people visited the salins last year. Even if you are not a foodie, you are undoubtedly aware of the world-wide interest in salt as a specific culinary product. Salins d’Aigues-Mortes is trying to ride this wave and has begun a campaign to attract even more visitors.

I confess I have not taken these tours, but they are on my list…especially after doing the research for this article. We have seen the salt marshes and, as I wrote in the

earlier post, a huge swath of the gorgeous Camargue.

After so much reading about salt, you might find that you have a hankering for something on the salty side. I suggest you check out David’s

Cocoa & Lavender post (about his salt addiction)…It features a recipe for Mark’s mother’s Salted Oatmeal Cookies. Now, which salt will you use?

_________________________________________

Notes:

“Aigues-Mortes, Un Port Pour les Croisades” (“Aigues-Mortes–A Port for The Crusades”) is a film about the history of Aigues-Mortes, created to help educate people about their visit to this city. It was released February 24, 2014. The website for the film offers a lot of information about Aigue-Morte’s history. For more information about time, prices and where to see this 20 minute movie in Aigues-Mortes, click here.

Parking is available just outside the walls for day visits (look along Blvd Diderot first) and inside (with a card from your hotel) for overnight visits.

Market days are Wednesday and Sunday (in the morning) on Avenue Frédêric Mistral, just outside the walls. Look for regional specialties such as

asperge “Celestine” (white asparagus grown in salty soil),

pomme de terre des sables (potatoes grown in the sand), and

carrotte des sables (carrots grown in the sand).

The Fête Votive begins the first Sunday in October and lasts several days. This event centers around the Camargue bulls. The “bull games” in Aigues-Mortes are bloodless–at least for the bulls. Called courses Camarguaise, bulls are brought into makeshift rings to face brave (or crazy?) folks called raseteurs who attempt to remove ribbons attached behind the horns of the bulls. We saw a course Camarguaise around Easter one year, but apparently they no longer take place in Aigues-Mortes in the spring. Often called La Feria, they are held in other parts of the Camargue and in nearby cities around Easter, along with Spanish style bull fighting.

Le Grau-du-Roi, a town just 6 km miles from Aigues-Mortes, is one of France’s most important fishing ports. It also boasts a Seaquarium, huge marina, the lovely Plage de l’Espiguette, and an 18th-century light house. (Ernest Hemmingway and his second wife Pauline honeymooned here.)

Wine

Wine production in the Camargue is documented to be in existence as early as the 15th century. The phylloxera epidemic that decimated so many of France’s vineyards did not affect those in Aigues-Mortes because the vines grow in the sand. Red, grey, rosé and white wines are produced in the region.

The predominant production at 94% of volume is for grey and rosé wines. The grey, sometimes referred to as the “grey of grey,” and rosé wines both have a pale salmon color and are described as having an “elegant mouthfeel and freshness”. Main grape varietals for the greys and rosés are Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Carignan Noir, Carignan Gris, Cinsault, Grenache Noir, Grenache Gris, Merlot, Syrah.

Red wines only make up 4% of production and are described as having soft tannins and being quaffable and aromatic. Main grape varietals for reds include Cabernet franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Grenache Noir, Merlot, Marselan, Syrah, Petit Verdot.

White wines make up only 2% of production and the main grape varietals are Chardonnay, Chenin, Clairette, Grenache, Marsanne, Muscat à petits grains, Muscat d’Alexandrie, Roussanne, Sauvignon, Ugni Blanc, and Viognier.

Wow – I had absolutely no idea that there was this much history in Aigues-Mortes! Other than our conversations and brief mentions in travel guides, I have heard nothing of it. And yet it is so touristed? That is such a surprise. Thanks, Susan, for a really terrific article – my silly meanderings on salt addiction pale in comparison to the research and work you have done here! So glad Towny made you the cookies so you could have one with your tea this evening! (Incidentally, they are wonderful with cocoa, too!) Bises, David

Oh, and Towny's photo of the salt cellars is absolutely stunning.

Really interesting, Susan! And wonderfully timed with David's post on Cocoa & Lavender. I have not explored the Carmargue, but it is on my bucket list. Thanks for giving me one more reason to go.

Whoever thought a story about salt could hold my interest so long? Great post, Susan!!! Your blog gets better all the time. Congratulations! MMN

Hello Susan,

I have been reading your posts for more than a year and enjoy them enormously. My wife and I spend a wonderful vacation traveling through France many years ago and spent three days with friends of friends in Bonnieux, at the time not yet overrun with tourists. I have wanted to comment on several of your posts but always seem to have difficulty navigating the comments section's maze.

The post about Aigues-Mortes was the latest to stir my interest. I grew up in a small village in Trinidad and Tobago in the Caribbean. My village had come into existence after the French revolution when the British, whose colony Trinidad was, invited the pro-Royalist French colonial planters fleeing their plantations in now republican colonies, to come to Trinidad. My forefathers came as freemen with several of these planters and they all were given land by the British.

The language of the village was French patois although most people could speak some English. Rereading The Count of Monte Cristo recently I noticed that Dumas seemed to attribute the deadly fever suffered by the wife of Caderousse, one of the major villains of the novel, to the dead water of Aigues-Mortes where their tavern was situated. It reminded me that in my village fever and chills were called "aigue" in patois and this led me to wonder if Aigues-Mortes really meant "deadly water" rather than "dead" or "stagnant water.

It is a long shot but it got me to write to you finally and to say "great stuff" and keep it up.

George Archer

Montreal, canada

Hi David, Knowing a little of the history of the area does make that fortified city come alive! To know that salt harvesting has been a the economic agent throughout its history–long before the tacky stores–is also very interesting. Bis, Susan

P.S. The salted oatmeal cookies (from your post) were wonderful!

Thanks Kirsten for the positive feedback. It is a very different area than the Luberon, where I know you have spent a lot of time. And yes, it was fun to coordinate with David's Cocoa & Lavender blog!

Salt is so common and seemingly uninteresting to all of us and yet its production and the roles it has played in history are anything but! Thank you for your nice feedback!

I very interesting post of an area I've been close to but never quite got there. I use Baleine salt on a daily basis so nice to know about where it comes from.

I am fascinated by the use of the word "aigue" to refer to fever and chills, a word so firmly ingrained in the patois of the people, that it is used in another land, across the ocean! Like you, I do wonder what its origin may be. In the mid-19th century, when Dumas wrote his book, there was apparently an outbreak of malaria and meningitus in the Camargue and in Aigues-Mortes, in particular (where there was greater population density) and it would be understandable if people attributed the cause to the dominant attribute of the area–stagnant water. (Undoubtedly, outbreaks of other diseases arose in the area, like other areas of Europe at that time.)

Does anyone out there have any thoughts on the matter?

Thanks so much for writing, George, and for such positive feedback.

Best regards,

susan

I, too, use Baleine salt and was interested in knowing where it came from and that the harvesting of that salt has such a long history! Thanks for your note, Karen!